Knot Worthy by Whiti Hereaka

*Note/Hint: The Rows are a coded message/spell for you to unravel and puzzle over.

Give me a knot and I will take the time to unravel it. I love the puzzle of it. To untangle a knot you need to understand it — the tension and release of it. Pull one loop tight to slacken the tension on another. Follow the loops and twists, to find the beginning of the yarn. Or the end. If you are patient and persistent, the path through the knot will reveal itself. I am patient. I am persistent. I will not cut the knot in half like Alexander. I am great at knots.

How to start:

Cast on 55 stitches.

How to start.

Every project starts with a knot. In knitting it is a simple slip-knot, in writing it is a question to answer.

When you first start knitting, you don’t start at the beginning at all. Casting on a piece demands that you already know how to form a stitch; that you already have the knowledge of the best type of cast on to use for your project: because how you cast on can affect the shape of your piece. The functionality of it.

I’ve started this many times, but I’m still unsure of the shape of it.

Cast on, frogged the stitches. Cast on, frogged again.

Perhaps I should do what I ask of my students — ask myself where the story actually starts, and why am I writing this? Why now?

Sometimes, you just need to write until you find the beginning. You might have spent hours, days writing your false start and so finding the true start paragraphs, pages, chapters in makes your stomach knot. But you can’t deny it, the true start, because all the threads lead to that point. You know why you’re writing this. You know why you’re writing it now.

Find a project that will forgive your mistakes. Find a project to hide your mistakes. Something that is more about the feel of the thing, rather than the purpose.

Row 1: K all sts

Row 2: K4, P to last for sts, K4

Row 3 and all odd rows to Row 35: K all sts

I’ve learnt to knit three times. The second time was when I worked at the haberdashery counter at Kirkcaldie and Stains. I choose the worst possible yarn to learn with, a silky, slippery, feathery yarn in almost fluorescent orange.

I was frustrated that my hands were clumsy and slow. I was scared of making a mistake. I had to force my needle through the stitches.

“You don’t need to hold your work so tightly,” Mrs McCullough said.

Row 4: K4, P5 YO P2tog K2 P2 K1 P1 K1; YO P2tog K2 P1 K2 P2; YO P2tog K2 P2 K2 P1, YO P2tog P1 K1 P1 K3 P1; YO P2tog P4; K4.

Last time we spoke we talked about fate and destiny, and how fate seems the more negative word. I think it’s because to think of fate you can’t escape The Fates and the idea that this life, this thread, that we are allotted — is already spun, measured and cut. Inescapable.

And it becomes something oppressive, suffocating, and overwhelming.

Row 6: K4, P5 YO P2tog P1 K1 P5; YO P2tog K2 P1 K2 P1 K1; YO P2tog K4 P2 K1; YO P2tog K3 P2 K2; YO P2tog P4; K4.

In the writing workshop I teach we talk about story. We talk about how humans are wired to seek story, to look for patterns. We talk about audience expectation and how to use the tools that we have — the very basic tools: words and sentences — to fulfil those expectations. Or to subvert them.

Row 8: K4, P5 YO P2tog K2 P1 K3 P1; YO P2tog K2 P2 K3; YO P2tog K2 P1 K2 P2; YO P2tog K2 P2 K1 P1 K1; YO P2tog P4; K4.

You don’t need a lot to start knitting: some needles, some wool, some patience. Knitting is cumulative: a piece of yarn is transformed stitch by stitch, row by row until you have the fabric of something.

Row 10: K4, P5 YO P2tog K3 P1 K1 P1 K1; YO P2tog K2 P1 K3 P1; YO P2tog K3 P1 K1 P2; YO P2tog K2 P4, K1; YO P2tog P4; K4.

I make my students walk their stories. The rhythm of it is not just in your mind, it is in your feet, it is in your body.

Row 12: K4, P5 YO P2tog K2 P1 K1 P2 K1; YO P2tog K2 P1 K2 P2; YO P2tog K2, P1 K2 P2; YO P2tog P1 K1 P5; YO P2tog P4; K4.

You don’t need a lot to start writing: some pens, some paper, some patience. Writing is cumulative: an idea of a yarn is transformed word by word, sentence by sentence until you have the fabric of something.

Row 14: K4, P5 YO P2tog P3 K1 P1 K1 P1; YO P2tog K1 P2 K1 P2 K1; YO P2tog P1 K1 P5; YO P2tog K3 P1 K3; YO P2tog P4; K4.

In class, I gift my students the terms for things they instinctually know: Freytag’s Pyramid, Hero’s Journey, Chekov’s Gun. They already know this because our lives are steeped in story, the rhythms of it are as familiar as our own heartbeat. And yet, who wouldn’t marvel at an echocardiogram? An image of your heart made whole out of sound. The rhythm, the rhythm is important.

Row 16: K4, P5 YO P2tog K2 P1 K4; YO P2tog K3 P1 K1 P1 K1; YO P2tog P1 K1 P1 K3 P1; YO P2tog P3 K2 P1 K1; YO P2tog P4; K4.

The knitting is supple and strong, it can move and stretch over the body. It gets its strength from each interlocking stitch — some stitches are pulled taut with tension, while others slacken. A dropped stitch threatens the entire fabric: everything could unravel.

Row 18: K4, P5 YO P2tog K3 P1 K1 P2; YO P2tog K2 P1 K1 P3; YO P2tog P1 K1 P5; YO P2tog K4 P2 K1; YO P2tog P4; K4.

I teach my students about the Kushlov Effect. We watch an expressionless man experiencing hunger, grief, desire.

Row 20: K4, P5 YO P2tog K2 P2 K1 P1 K1; YO P2tog P1 K1 P5; YO P2tog K3 P1 K3; YO P2tog K2P1K1 P2 K1; YO P2tog P4; K4.

The writing is completing itself in your mind, it moves and stretches to find a story. It gets its strength from your expectations, and the rhythm already established. This is a risk, I’ve handed you the power and now everything could unravel.

Row 22: K4, P5 YO P2tog P1 K1 P5; YO P2tog K2 P1 K2 P1 K1; YO P2tog K2 P4 K1; YO P2tog K2 P2 K1 P2; YO P2tog P4; K4.

These are the knots I cannot untangle: the one in my stomach, the one that entwines my heart and the one that ties my tongue.

Row 24: K4, P5 YO P2tog K2 P1 K4; YO P2tog K3 P1 K1 P2; YO P2tog P1 K1 P5; YO P2tog K1 P2 K1 P2 K1; YO P2tog P4; K4.

We’re chatting about knitting and I tell him about how it was used as a code in WWII. Except I get the threads of the story tangled — codes weren’t sent via knitting pattern, although the British did ban knitting patterns in WWI because they thought patterns might be used that way. How easy it would be to hide messages amongst k1, p2, M1R, sl1pwyif — who, but a knitter could crack that enigma?

Knitting espionage was physical and simple: a dropped stitch, a purl stitch. Knitting lends itself to Morse code, to binary. Knit one, purl one. Knots tied in yarn at certain intervals hidden in rewound balls of yarn, or within a knitted object itself: the message hidden until the garment was unravelled.

Mostly, knitting was used for cover. Women already become invisible as we age — knitting just amplifies it.

Row 26: K4, P5 YO P2tog K3 P2 K2; YO P2tog P1 K1 P5; YO P2tog K2 P1 K1 P1 K2; YO P2tog K2 P1 K3 P1; YO P2tog P4; K4.

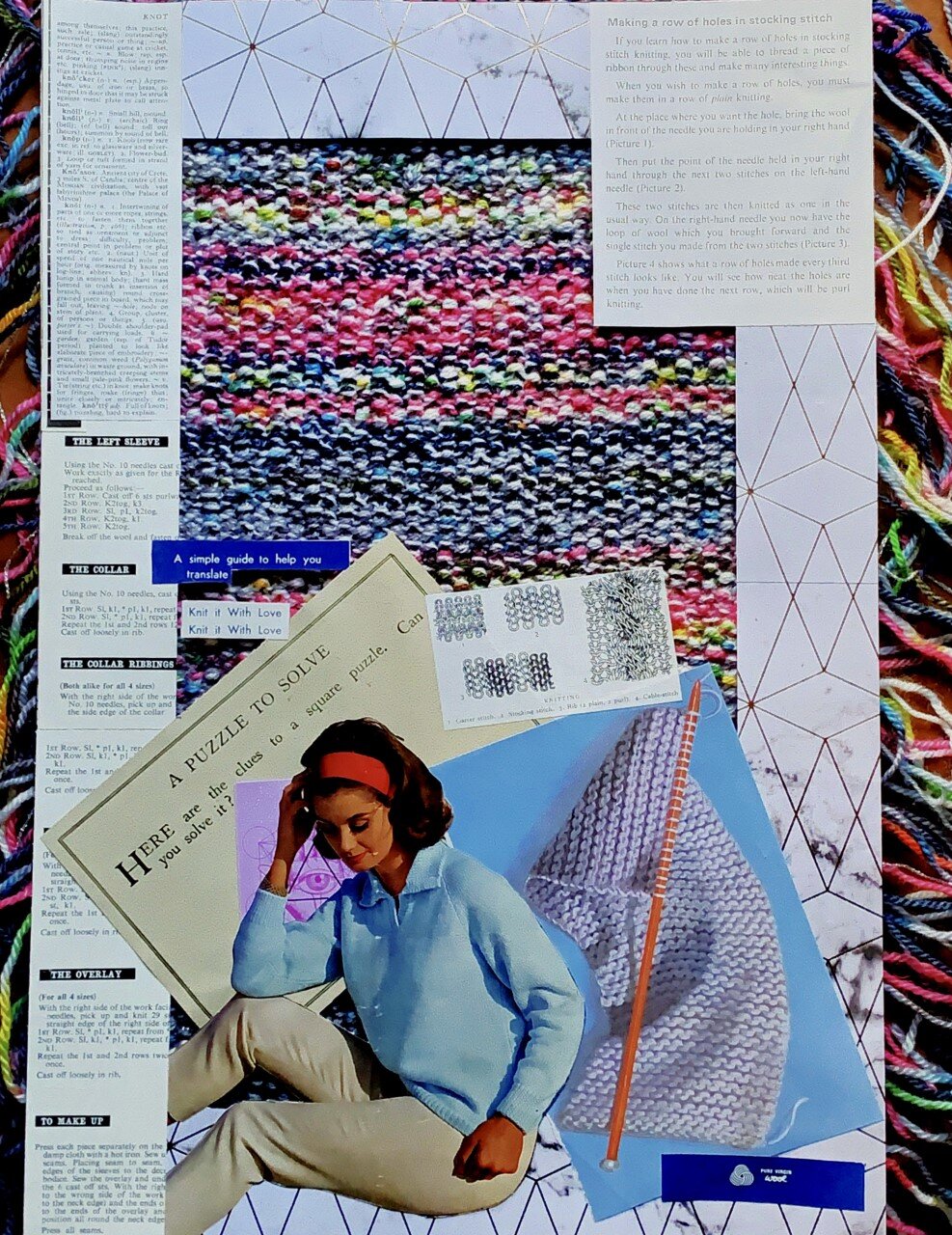

This year I decided to knit a mood scarf. It was a simple idea: knit a row a day in a colour that corresponds to the mood I felt. I wanted to remember how I actually felt each day — my memory dulls my emotions. I can only remember a numb greyness day to day.

It is an attempt to make the ephemeral permanent, to make the passage of time physical.

2020 was the worst year to start a mood scarf.

I didn’t know it would become a record of a global mood. I didn’t know that simple act of knitting a row of stitches a day would help to ground me when the days seemed to be both never ending and passing too quickly. I can see each day and feel it under my fingertips. Eventually I will let the year envelop me.

Row 28: K4, P5 YO P2tog P1 K1 P5; YO P2tog K3 P1 K1 P2; YO P2tog K2 P1 K1 P3; YO P2tog K2 P1 K1 P2 K1; YO P2tog P4; K4.

My mother is left-handed and I’m not, so my nana teaches me to knit the first time.

One of the stories my family tell when they want to explain me is that I start a lot of things but I never finish them.

Perhaps the knitting lessons are the start of that story, I can’t remember finishing that project. I don’t actually remember the lessons themselves, just some random feelings: the scratchy, red wool, trying the force my needles through the stitches because my tension was so tight.

I was scared of making a mistake. I was frustrated that my hands were clumsy and slow.

Row 30: K4, P5 YO P2tog K2 P1 K3 P1; YO P2tog K3 P1 K1 P2; YO P2tog K2 P2 K1 P1 K1; YO P2tog P4; K4.

I’m reading some questions for an interview I’m recording tomorrow. One of the questions is: Where do you get your ideas from? It’s a question that I dread — because I know what they want from me: a map, a formula to follow. And I could just give them that, but I want to be truthful as well: because I’ve never suffered from a lack of ideas — my problem is that I have too many ideas. Anything can be fascinating. I accumulate ideas and thoughts, follow threads through labyrinths, lose my path. My problem is that all my ideas become oppressive, suffocating, and overwhelming.

Row 32: K4, P5 YO P2tog K2 P1 K2 P2; YO P2tog K2 P1 K2 P2; YO P2tog P1 K1 P5; YO P2tog K3 P1 K1 P1 K1; YO P2tog P4; K4.

If you can unravel something, can you ravel it? The unravelling of a thing is often revealing.

Ravel.

Reveal.

Revile.

Row 34: K4, P5 YO P2tog K1 P2 K1 P2 K1; YO P2tog P1 K1 P5; YO P2tog K3 P1 K3; YO P2tog K2 P1 K1 P2 K1; YO P2tog P4; K4.

Cornish witches use knitting as a form of spell craft. They use blunt glass needles to knit, repeating their incantation with each stitch or row. The spell gets its power from the repetition, focus and the meditative state of the witch.

There are still remnants of that old magic in modern knitting. A twee version of a knitting hex that is sometimes called The Boyfriend Sweater Curse. I prefer The Curse of the Love Sweater, which sounds like the title of a bodice ripper. It’s not just sweaters that are cursed — although the amount of time spent on a sweater probably contributes to their bad luck. Anything knitted as a love token can be cursed: a scarf, a hat or a pair of socks.

It is said that the relationship between the knitter and those they knit for will unravel before it is finished. It is the knitter that is cast off.

The object is irrefutable proof that the knitter dared to love: it is there in every stitch. It is an oppressive, suffocating, overwhelming reminder.

I don’t see it as a curse, instead I see it as a test: are you knit-worthy, or not-worthy? Are you worth my time, my effort? Are you so damaged that the thought of someone caring for you scares you away?

Besides, if I was going to curse you I’d be upfront about it.

Work rows 1 – 35 10 more times or until piece is as long as desired.

I knit him socks. The wool and needles are my constant companions for months. He is not.

Last row: K all sts.

Graft live stitches to cast on stitches.

2020 is the year I’m learning to knit for the third time — switching from English to Contential knitting. Holding my wool in this new way makes my hands slow and clumsy, they are so used to the old way. I’m unlearning the things I was taught as a child and again as a young adult. I’m asking my hands to forget over twenty years of accumulated muscle memory, in the hope that eventually I’ll be able to knit faster and more efficiently.

I have to focus even when I pick up my needles — holding my yarn in my left hand feels so unnatural. And it is increasingly difficult for me to focus on anything this year.

One stitch at a time. That’s all I need to concentrate on. Just this stitch.

Weave in ends.